On childhood, devotion, and the quiet reorientation of contemporary Indian art

New Delhi [India], January 27: Every civilisation produces artists who decorate its time and a rare few who quietly recalibrate how that civilisation sees itself.

Rajat Pandey belongs unmistakably to the latter category.

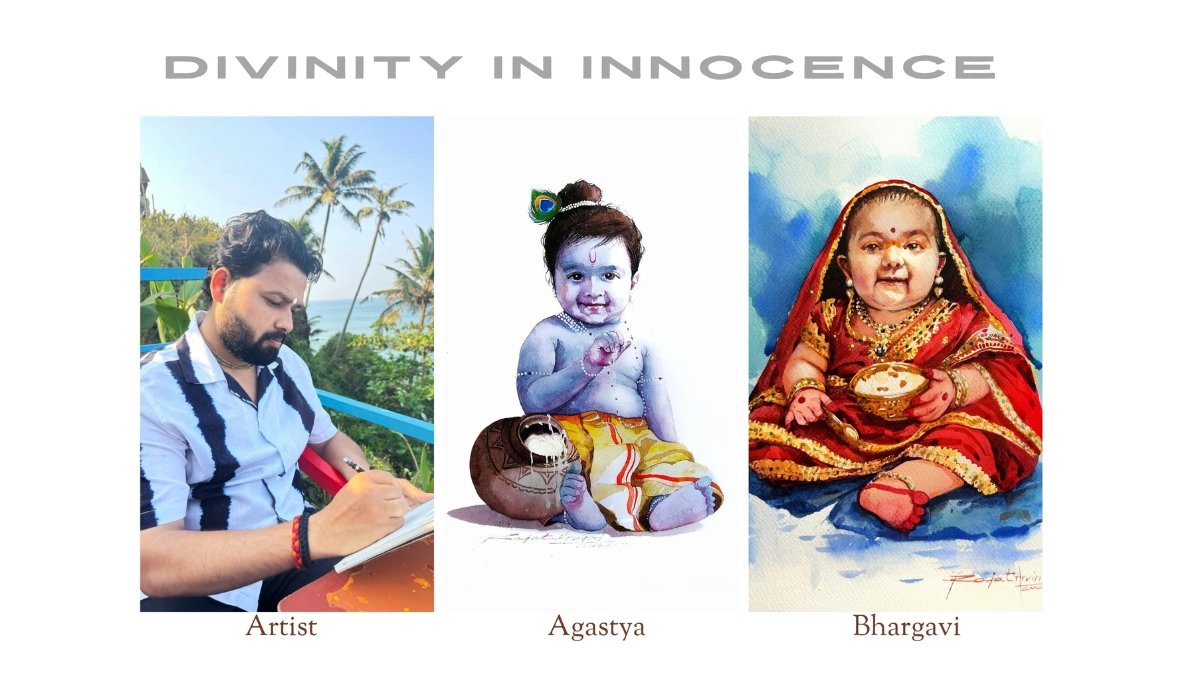

His recent body of work, Divinity in Innocence, does not announce a new style or manifesto.

Instead, it signals something more consequential:

the return of the sacred eye to contemporary Indian art after decades of irony, rupture, and aesthetic self-consciousness.

This is not unfamiliar territory in art history.

Raja Ravi Varma once redefined how myth could inhabit realism. Later, artists like M.F. Husain and S.H. Raza abstracted the sacred into movement and geometry, allowing Indian art to converse with modernity without abandoning its metaphysical core.

Each, in his own time, addressed the same civilisational question through different visual grammars.

Pandey approaches that question from an entirely different direction: through childhood.

In his portraits of Agastya and Bhargavi, created around the ritual of Annaprashan, divinity is neither monumental nor symbolic. It is embodied.

The figures do not perform godhood; they inhabit potential. Innocence becomes ontology.

This is a critical departure. Where modern art often sought transcendence through abstraction or scale, Pandey locates it in proportion, restraint, and intimacy.

The sacred is not imposed; it emerges.

Art history reminds us that such shifts are rarely loud.

Giotto did not declare the Renaissance; he humanised the divine.

Michelangelo did not illustrate theology; he embodied it in flesh.

Van Gogh did not paint madness; he reorganised perception through intensity and devotion.

Pandey’s work operates within this lineage of quiet recalibration.

His training at Banaras Hindu University places him firmly within India’s most rigorous artistic parampara, yet his present life as an educator in Tamil Nadu extends his role beyond authorship.

He is not only producing images, but transmitting a way of seeing—one that treats painting as discipline, responsibility, and offering.

Importantly, Pandey resists the contemporary impulse to aestheticise tradition.

He does not quote mythology; he lives within its moral architecture. This distinction—between reference and inhabitation—is what separates historical artists from stylistic ones.

If modern Indian art spent the twentieth century asserting its freedom from the past, the twenty-first will belong to artists capable of returning to it without regression.

Rajat Pandey’s work suggests that such a return is already underway.

Not as revival.

Not as nostalgia.

But as necessity.

If you object to the content of this press release, please notify us at pr.error.rectification@gmail.com. We will respond and rectify the situation within 24 hours.